It’s no secret that the Academy Award for Best Picture seldom goes to the most deserving film that year. Indeed, this is the same Academy that opted for Dances With Wolves over Goodfellas, Shakespeare in Love over Saving Private Ryan, and Crash over… well, not Crash.

Every so often, though, its members manage to pull through and make the correct call. Whisper it, as examples really are rare – but here are 12 times the best picture actually won Best Picture.

2016 – Moonlight

2016 was a stellar year for filmmaking – from Arrival to Hell or High Water, the range of quality genre films on display was truly special. As such, Best Picture was always shaping up to be a fiercely contested category.

La La Land had been the firm favourite throughout awards season, yet it was Moonlight which triumphed on the night. The two are undoubtedly the cream of the crop from the year, but attempting to compare the two is a difficult task (not to mention completely beside the point). The more appropriate action would be to applaud both films for being the masterpieces they are, and for the vision and perseverance of their respective directors – with Damien Chazelle having spent 6 years trying to get La La Land made, and Barry Jenkins in his first directorial outing since 2008.

The film follows Chiron in three stages of his life (portrayed by Alex Hibbert, Ashton Sanders and Trevante Rhodes), as he struggles with his sexuality and an emotionally abusive mother (Naomie Harris). Moonlight is a groundbreaking achievement, exploring themes that are scarcely covered in Hollywood while being a stunning feature in its own right. Mahershala Ali manages to make his paternal drug dealer, Juan, an almost omnipresent being for the whole film, despite only appearing in its first act – while Nicholas Britell’s harrowing score and James Laxton’s work as DP fuse to magnificent effect.

2014 – Birdman or (The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance)

2014 was a similarly fantastic year – with the likes of The Grand Budapest Hotel, Interstellar and Whiplash. The year also marked the second coming of Michael Keaton, whose fantastic turn in Birdman or (The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance) was as acclaimed as the film itself. Revolving around a washed up, box office star in his attempt to reinvent himself as lead actor/writer/director on Broadway, the film is an incredible, meta look at fame and popularity as a means of success.

Along with Keaton, Birdman‘s supporting cast is outstanding – the always-great Edward Norton has a superb dynamic with both Keaton and Emma Stone, while Zach Galifianakis utilises his successful background in comedy for his role as Jake, although with a little more nuance.

Boyhood – its main rival for the prize at the 87th Academy Awards – largely delivered on its highly ambitious scope of filming the cast over an 11-year period; although once the audience gets over this impressive feat, the film is admittedly unspectacular. Its subsequent rewatchability isn’t the best – especially once put up against something like Birdman, which simply seems to get better with each viewing.

2006 – The Departed

A remake of the 2002 Hong Kong crime-thriller Infernal Affairs, Martin Scorsese’s The Departed is a rare case in cinema of successful Americanisation. Undoubtedly aided by the ingenuity of Infernal Affairs’ original plot, it is the strength of the film’s A-list ensemble cast that really makes The Departed the quality feature it is – so strong, in fact, that Jack Nicholson was billed only third.

Scorsese-regular Leonardo DiCaprio unsurprisingly excels as Billy Costigan, an undercover cop who infiltrates the Irish Mob – headed by Frank Costello (Nicholson), a formidable presence who also acts as the paternal figure to the mobsters. Simultaneously, Costello has sent a mole (Matt Damon) to work his way up into the police force. The twists and revelations that follow are simply genius, whilst Mark Wahlberg steals the show as foul-mouthed police detective, Dignam.

The title of 2006’s best film was fiercely contested, with Clint Eastwood’s Letters from Iwo Jima and Mel Gibson’s Mesoamerican epic Apocalypto proving worthy competitors. However, The Departed was deservedly crowned as Best Picture, whilst also delivering for Scorsese his long overdue award for Best Director – a worthy recipient if ever there was one.

2003 – The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King

Peter Jackson’s epic fantasy completely cleaned up at the 76th Academy Awards, winning every single one of its 11 nominations to join Ben-Hur and Titanic as the most awarded films in Oscar history.

The ensemble cast all deliver worthy performances – notably Ian McKellen as Gandalf the White, as well as Viggo Mortensen’s eponymous king-in-waiting Aragorn – but this is a film that excels through sheer spectacle, rather than the particulars of its cast.

Cases could admittedly be made for the likes of Lost in Translation and Mystic River, while Kill Bill: Volume 1 was completely shut out by the Academy. But for sheer scale alone, The Return of the King is thoroughly deserving of its golden statue. Consistently delivering in its epic set-pieces, the final instalment of the Lord of the Rings trilogy somehow manages to top the extremely high bar set by its predecessors – and then some.

1993 – Schindler’s List

The story of a German businessman using his position to rescue Jews from the Holocaust, Schindler’s List is a harrowingly beautiful look at a time in which little else can be admired. Director Steven Spielberg’s traditional optimism and sentimentality are thoroughly welcome here, bringing the heroics of Oskar Schindler into the public consciousness.

Liam Neeson does the titular hero plenty of justice in a career-best performance, whilst Ralph Fiennes’ plays Amon Göth – SS captain and commandant of the Płaszów concentration camp – down to a tee, with suitable abhorrence. Also of note is John Williams’ phenomenal score, with its theme perfectly encapsulating the tone of the film in a mere 4 minutes.

Despite both Neeson and Fiennes missing out on the acting gongs to Tom Hanks and Tommy Lee Jones, respectively, Schindler’s List was duly awarded Best Picture by the Academy. Interestingly enough, 1993’s next best feature is Spielberg’s other release that year (a little flick by the name of Jurassic Park) – a remarkable output from the prolific director.

1992 – Unforgiven

Clint Eastwood’s swan song to the Western, Unforgiven utilises the ‘one last job’ trope to magnificent effect in this tale of retirement, reputation and vengeance.

As well as directing, Eastwood stars as the aging gunslinger, Will Munny, hired to dispose of the troublesome cowboys who have been terrorising the town of Big Whiskey. Aided by his old ally Ned Logan (Morgan Freeman), the pair soon realise their abilities are not what they once were. The two are exceptional in conveying both their physical and mental frailties, whilst Gene Hackman is equally superb as local sheriff/antagonist, Little Bill.

Eastwood doesn’t shy away from Unforgiven‘s influences, instead wearing them proudly on its sleeve – culminating in a “to Sergio [Leone] and Don [Siegel]” dedication in the credits. The two late greats were instrumental in Eastwood’s acting success: from his lead role in Leone’s Dollars trilogy (1964-66) to Siegel’s Dirty Harry (1971), a role he continued playing until 1988. Both roles heavily revolved around antihero narratives – indeed, characters not unlike Unforgiven‘s Munny.

Make no mistake, however – Unforgiven is not merely a mimicry of previous greats; rather, Eastwood using his vast experience of the genre to deliver one final entry to rival them all. If this is his tribute to his former mentors and to the Revisionist Western, what a brilliantly fitting one it is.

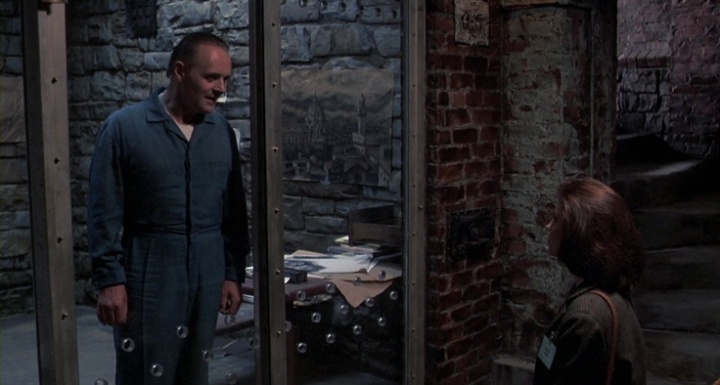

1991 – Silence of the Lambs

Only the third film in history (and, to date, most recent) to win the Big Five – Best Picture/Director/Actor/Actress/Screenplay – Silence of the Lambs follows young FBI trainee Clarice Starling (Jodie Foster) as she attempts to track down serial killer Buffalo Bill, enlisting the help of Anthony Hopkins’ Hannibal Lecter – a former serial killer himself (albeit incarcerated).

What ensues is a morbidly thrilling game of cat-and-mouse, with Hopkins particularly dominating proceedings – despite his appearance only clocking in at around 16 minutes long (indeed, being one of the briefest Oscar-winning performances in history).

Competition that year was admittedly on the weak side, highlighted (arguably) by an animated film, Beauty and the Beast, picking up a nomination for Best Picture for the first time. Nevertheless, Silence of the Lambs has stood the test of time as a fine feature – with Hannibal Lecter an iconic figure in popular culture.

1974 – The Godfather Part II

Although not as rare as it’s often made out to be, sequels tend to not match up to the original – let alone better them. And although I’m of the opinion that the first Godfather is the best in the series, boy does Part II give it a good run for its money.

Removing its predecessor’s standout aspect in Marlon Brando, it’s extraordinary the film is as stunning as it is. Perhaps it’s the addition of one Robert De Niro, playing a younger incarnation of Brando’s Vito Corleone. Perhaps it’s the more ambitious narrative, intelligently crafted to satisfy as both a sequel and prequel. One thing’s for sure: The Godfather Part II is an outstanding picture, managing to complement (even improve) the original, whilst also not reliant on the glorious success of its predecessor.

Arguably even more impressive is the fact that it rightfully won the top prize in 1974 – a sublime year of cinema that included Chinatown, The Conversation and Blazing Saddles.

1972 – The Godfather

Easily one of the greatest films in the history of the medium, Francis Ford Coppola crafted nothing short of a masterpiece with The Godfather. Sparking a much needed resurgence in the genre, this crime epic charts the clandestine dealings of the Corleone family – headed by Marlon Brando’s Don Vito.

Al Pacino marked his name as one of the finest working actors with a superbly nuanced performance as Michael, Vito’s youngest son who is reluctantly drawn back into the criminal underworld. James Caan is extremely fierce as Sonny, the hot-headed eldest son, while John Cazale shows why he is regarded as one of the best character actors of all time, in his role as the dim-witted middle son, Fredo. Robert Duvall is predictably solid as family lawyer/voice of reason Tom Hagen – but it is inevitably Brando who steals the show, in his now-iconic performance as the Don.

All of this – including Nino Rota’s immortal score and Gordon Willis’ magnificent use of dark lighting – coalesce to produce one of the finest films the industry has ever seen. Although 1972 produced other gems such as Solaris and Deliverance, there is no doubt that the award for Best Picture went to the worthy candidate; perhaps the greatest winner in the ceremony’s history.

1969 – Midnight Cowboy

The first R-rated film to win Best Picture, Midnight Cowboy tells the story of Jon Voight’s young Texan, who heads to New York City to find more profitable work as a prostitute – fully clad in cowboy attire. There, he encounters despicable con man Rico ‘Ratso’ Rizzo (Dustin Hoffman), and the two work together as hustlers.

While an incredibly bleak affair – with Ratso’s health increasingly deteriorating – there is warmth to be found in the friendship formed between the two struggling leads. Along with Hoffman’s performance, the soundtrack is another standout from the film – namely the score from John Barry.

A slight cut above the year’s other best films – particularly other New Hollywood stalwarts, such as Easy Rider and Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid – Midnight Cowboy thrives on the stellar performances of Hoffman and Voight; its gritty, dogged story showcasing New Hollywood’s penchant for conventionally unattractive leads and a deviation from traditional narratives.

1962 – Lawrence of Arabia

Based on the real experiences of T. E. Lawrence during World War I, this sprawling epic is perhaps the crowning masterpiece of David Lean’s extraordinary career. Peter O’Toole stars as the titular Lawrence, a British Army lieutenant sent to the Arabian Peninsula to gather intelligence on the Arab Revolt.

Lawrence becomes increasingly conflicted between allegiances – with his Arabian comrades growing suspicious of the British Empire’s true intentions – and O’Toole conveys this excellently. Omar Sharif is equally as brilliant as Sherif Ali, a fictional character intended to be an amalgamation of several real Arab leaders; while Alec Guinness and Anthony Quinn provide memorable support as Prince Faisal and Auda abu Tayi, respectively.

Anne V. Coates’ immortal match cut gave us perhaps the most famous edit of all time, while the awe-inspiring cinematography from Freddie Young produced some of the most iconic shots in cinematic history – marvellously accompanied by Maurice Jarre’s monumental score.

In any other year, the likes of Lolita, To Kill a Mockingbird and The Man who Shot Liberty Valance would all be worthy winners, but the consistent across-the-board quality of Lawrence of Arabia‘s whole production make it the most outstanding feature of 1962.

1957 – The Bridge on the River Kwai

The first of his five epics, The Bridge on the River Kwai showed the world that David Lean – then known for his smaller scale dramas like Brief Encounter and Great Expectations – had a deft eye for the spectacular. A fictional work based on the historic construction of the Burma Railway, the film revolves around a group of British POWs, led by Alec Guinness’ Lieutenant Colonel Nicholson, who are made to build a bridge for their Japanese captors.

Guinness gives one of the best performances of his career as Nicholson, a stubborn leader who begins to take a curious sense of pride in the bridge’s construction. William Holden is just as impressive as US Navy Commander Shears, who manages to escape the prison camp before being starkly informed he must return to destroy the bridge – while Jack Hawkins and Sessue Hayakawa are both superb in their supporting roles as Major Warden and Colonel Saito, respectively.

Whilst solid throughout, it is in the final act of the film in which it truly flourishes – with Shears’ commando mission clashing with the huge sense of achievement felt by Nicholson and the other prisoners. A remarkable feature from the master of the epic.

March 16th, 2017.